Micro-credentials are an important response to social, economic, and technological changes.

Why did NZQA add micro-credentials to the New Zealand Qualifications Framework three years ago, and what have we learned?

Download this paper as a PDF:

Aotearoa New Zealand’s rationale for micro-credentials: Insights paper [PDF, 919 KB]

On this page

Introduction

Micro-credentials are small units of learning, consisting of between 5 and 40 credits. Smaller than a full qualification, they are designed to allow recognition of a discrete set of skills that meet specific learner, employer, industry or iwi needs.

Micro-credentials can supplement full qualifications by rapidly responding to the evolving skills needs of industry, particularly in response to technological changes. They enable learners to upskill and reskill at different stages of their lives, which benefits learners, employers and the community. Lifelong learners benefit from official recognition of shorter programmes so that they can carry evidence of their new skills with them into existing and future jobs. Stackable micro-credentials offer learners more flexible pathways to achieve full qualifications, which may help support equity of educational outcomes for underserved learners.

In this paper, we describe what Aotearoa New Zealand hoped for from the introduction of micro-credentials, and reflect on our progress in achieving those desired outcomes. Another Insights Paper Improving relevance and responsiveness: New Zealand’s early micro-credentials journey (New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2022a) illustrates through a series of short case studies how learners and employers have benefited from micro-credentials.

Tertiary education challenges

Aotearoa New Zealand, like other countries, faces a range of challenges and opportunities in its postsecondary education:

- A skills mismatch to jobs contributes to low national productivity

- Traditional tertiary education policy settings have particularly focused on younger learners in full time study over lifelong learners

- The tertiary education system struggles to deliver equitable outcomes for Māori, Pacific and disabled learners

- Lifelong learning can mitigate the risk of social cohesion being undermined

- Limited recognition and variable quality assurance of shorter skills programmes.

Skills mismatch to jobs contributes to low national productivity

Since the 1950s, New Zealand has dropped from being one of the world’s most productive countries to below the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) average (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2021). While the reasons for this are complex, one factor that limits New Zealand’s productivity is a high incidence of skills mismatch to jobs. This skills mismatch is one of the highest in the OECD (Earle, 2020) and indicates a ‘disconnect between the education system and the skill requirements of firms’ (Conway, 2018, p. 52).

Traditional tertiary policy settings have particularly focused on younger learners in full time study over lifelong learners

In 2017, the New Zealand Productivity Commission’s investigation into new models for New Zealand’s tertiary education concluded that the existing system focused on meeting the needs of school leavers studying full-time on campus and was not well suited to lifelong learning. Specific examples given were funding rules that make recognition of prior learning difficult and only fund providers when they enrol students in whole qualifications, and the design of the student support system (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2017).

A second New Zealand Productivity Commission report looked at how Aotearoa New Zealand might respond effectively to technological changes and the future of work (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2020). It observed that educational products tended to assume that education and training would happen soon after a learner leaves school, and only needed to happen once. The authors noted a need for educational products to better support lifelong learning, including accumulation of credentials at higher and lower levels over a person’s lifetime. They saw it as important to offer portable credentials that recognise existing skills and support ongoing upskilling. The report concluded that while adult New Zealanders have high overall rates of training, more qualified workers participate than unqualified workers, thus increasing existing inequity.

The tertiary education system struggles to deliver equitable outcomes for Māori, Pacific and disabled learners

New Zealand aspires to equity of outcomes for all New Zealanders. At present, Māori, Pacific and disabled people do not experience education equity, which further leads to inequity of income and wellbeing.

After completing school, half of Māori are now achieving a tertiary qualification by age 25, which is slightly lower than non-Māori school leavers (58%) (Green & Schulze, 2019, p. 5). However, Māori are achieving lower-level qualifications at a higher rate than non-Māori (Green & Schulze, 2019, p. 5). This begins in schooling, with Māori achieving university entrance at just under half the rate of European and Asian learners (New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2022b). There are however, encouraging trends. Young Māori students are leaving the education system more qualified than older Māori people (Stats NZ, 2020a). Māori are moving from low-skilled jobs to skilled and high-skilled jobs, with the number of Māori in high skilled jobs doubling between 2006 and 2018 (Reid et al., 2020, p. 24). This trend towards higher-skilled work is important for Māori because low-skilled jobs offer lower income and are most at risk of being replaced by automation. It is also important for all of Aotearoa New Zealand, because Māori are a young population and will be the backbone of the future working age population (Reid et al., 2020, p. 7).

Pacific peoples are a rapidly growing population in Aotearoa New Zealand, a diverse population made up of more than thirty distinct Pacific ethnic groups (Stats NZ, 2018a). Some Pacific learners are achieving, but the system is failing many Pacific learners. Achievement disparities in schooling translate into disparities in tertiary education, which link to further disparities in labour market participation, income and living standards (Ministry of Education, 2020, p. 2). Pacific people are less likely to be qualified and more likely to have a lower-level qualification than non-Pacific (Stats NZ, 2018a). As we observe for Māori, there are encouraging trends for Pacific people, with the percentage of New Zealand born Pacific people with a qualification at Level 3 or above increasing from 33% to 51% between 2006 and 2018. The level of qualification is rising, with the percentage of Pacific people with a degree or postgraduate qualification almost doubling over the same period (Stats NZ, 2018a).

In 2018, wellbeing outcomes for disabled adults aged 15-64 years were significantly lower than for non-disabled adults (Stats NZ, 2018b). Here, disabled people were defined as those who had a lot of difficulty, or could not do at all, at least one of six specified activities (6% of New Zealanders). These activities were seeing (even with their glasses), hearing (even with their hearing aid), walking or climbing stairs, remembering or concentrating, selfcare, and communicating (Stats NZ, 2020b). Median income for disabled adults aged 15-64 years was half that of non-disabled adults in the same age group (Stats NZ, 2020b). This is in part driven by disabled adults experiencing lower labour participation, higher unemployment, fewer hours worked each week and greater under-utilisation. Lower education attainment contributes to poorer labour market outcomes. Disabled people were less likely to hold a formal qualification (60%) than non-disabled people (83%) and less likely to hold degree-level qualifications (10%) than non-disabled people (28%) (Stats NZ, 2020b). Māori and Pacific people had higher-than-average disability rates, after adjusting for differences in ethnic population age profiles (Stats NZ, 2014).

Lifelong learning can mitigate the risk of social cohesion being undermined

Equal outcomes are important for communities as well as for individuals. Entrenched and growing inequalities, alongside increasing diversity in population, and rapidly emerging technologies risk undermining Aotearoa New Zealand’s social cohesion. The ‘rapid emergence of the relatively ungoverned virtual world’ (Gluckman et al., 2021, p. 3) gives opportunities for misinformation and disinformation and greater polarisation. Technology driven changes are ‘rapidly altering the constraints which helped glue societies together’ (Gluckman et al., 2021, p. 3).

Lifelong learning has a role to play in increasing social cohesion. Political and digital literacy are crucial for a healthy democracy (Gluckman et al., 2021). As New Zealand’s immigrant-related diversity grows, participation in tertiary and adult education for host and migrant communities is seen as one indicator of socially cohesive behaviour (Spoonley et al., 2005). A 2020 report on sixty years of adult learning in Aotearoa New Zealand noted the need for policies to ‘address the reality of adults who are having to learn a whole new range of skills and attitudes including learning at home, being parents as teachers, acquiring new technology skills, growing empathy and compassion for others and stepping up as active citizens to respond to the effects of the pandemic’ (Amundsen, 2020, p. 508).

Limited recognition and variable quality assurance of shorter skills programmes

In Aotearoa New Zealand, formal qualifications have a minimum credit value of 40-credits or an estimated 400 hours of learning. Historically, there have been a plethora of sub-qualification short courses offered by registered and non-registered education and training organisations and industry. Some of these have well established, global reputations as providers of quality certifications, for example Microsoft and other software certifications. Other examples are those required by registration and licensing bodies for continuing professional education. Much of this activity is informal with minimal regulatory oversight.

Short courses included NZQA approved ‘Training Schemes’, which were developed by providers and had a relatively low threshold for evidence of industry support. External evaluation and review of tertiary providers might include quality assurance of these short courses. However, because training schemes were not added to the then New Zealand Qualifications Framework (NZQF), it was difficult for stakeholders to know what existed and how to benefit from a scheme’s availability. Training schemes were not included on a learner’s Record of Achievement, so learners did not get the full benefit of recognition of their study.

Irrespective of the specific sub-qualification short course arrangements over time, there has been a need to provide a more regularised approach to supporting quality, transparency and portability.

The role of micro-credentials in change

Context of innovation

Aotearoa New Zealand has a rich history of innovation in vocational education qualifications and quality assurance. In the 1990s, it was one of the first countries to establish a national qualifications framework, and to embed competency-based assessment. In 2009, it was an early adopter of self-assessment as an integral part of organisational quality assurance. In 2017, NZQA established Te Hono o te Kahurangi, offering organisations the choice between standard quality assurance processes and processes based on te ao Māori approaches and values.

Innovation starts with informed risk taking with the potential for failure. NZQA seeks to ‘fail forward’ through learning from what does and doesn’t work from new approaches which then inform iterative improvements (“Intelligent Failure,” n.d.). One of the differences between failing and failing forward is having a hypothesis to test, iterate as needed and chart a new course when necessary. This includes use of data to test assumptions, guide activities and inform decisions (Hayes et al., 2016). NZQA’s levers to stimulate broader education and training system innovation include legislation and rules, the New Zealand Qualifications and Credentials Framework (NZQCF), NZQA processes and monitoring and evaluation.

Globally, there is a growing interest in shorter learning experiences to address challenges facing skills systems (Brown et al., 2021, p. 228). This trend has been accelerated by the pandemic with changing patterns of employment and urgent upskilling needs (Brown et al., 2021, p. 228). Prior to the pandemic, in 2018, following pilots and consultation, Aotearoa New Zealand was one of the first countries to introduce micro-credentials as part of a regulated education and training system.

The theory behind Aotearoa New Zealand’s approach to micro-credentials anticipates improved outcomes for industry, individuals, communities and the skills system. At the heart is formally recognised, quality assured, short courses with evidence of industry or community demand, which can stack (if appropriate) towards larger qualifications.

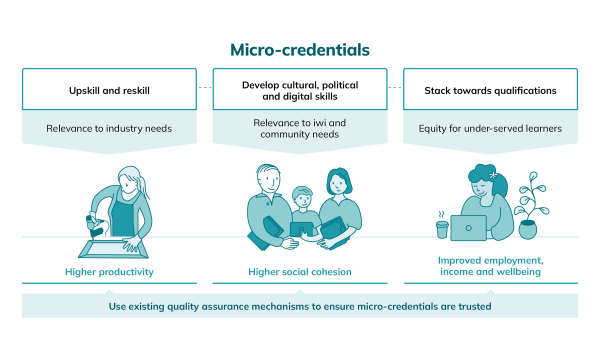

Figure 1: Theory of change for micro-credentials in Aotearoa New Zealand

Such micro-credentials increase the relevance of educational products. Micro-credentials developed with industry can more rapidly respond to emerging needs and enable lifelong learners to upskill and reskill throughout their lives. This will reduce the skills mismatch and thus improve productivity. Micro-credentials enable government and community organisations to respond to changes in civil society, and new entrants to Aotearoa New Zealand to upskill and reskill. This decreases the likelihood of lower social cohesion over time.

Assuring the quality of micro-credentials supports formal recognition and portability of skills development beyond first, larger qualifications. Individuals can carry a greater range of learning with them throughout their lives and employers can better understand and trust skills developed. This leads to an improved skills system that better supports a greater range of skills development needs.

Micro-credentials increase equity by reducing barriers to gaining qualifications through more flexible pathways to gaining awards. Learners who are not able to study full time or want to test their ability to fit study into their budgets and time commitments can gain recognition for small chunks of learning as they build towards a larger qualification.

Finally, these new ways of working need to be achieved in a sustainable way. This is achieved in Aotearoa New Zealand by building on existing infrastructure and quality assurance approaches. The European Training Federation’s (2022) survey identified comparable benefits, concluding that micro-credentials:

- Have immediate relevance to labour market demand

- Support individual learning

- Have stand-alone value

- Facilitate recognition of an individual’s skills, knowledge and competences

- Facilitate the design of flexible training

- Save cost and time.

Increasing relevance

The main driver for Aotearoa New Zealand’s introduction of micro-credentials in 2018 was increasing relevance of education products for employers, industry, communities, iwi, and learners.

Arguably, Aotearoa New Zealand had been well served by long standing systems for employer input into national qualifications, with regular review processes and strong quality assurance arrangements in place. At the same time, a case could be made that some qualifications had been too slow to market, unnecessarily long in duration and didn’t always result in the optimal balance of knowledge, skills and attributes sought by industry. The New Zealand Productivity Commission (2020) concluded that short training courses were a way to support lifelong learning and thus help New Zealand respond effectively to technological changes and the future of work.

Full qualifications offer new entrants a coherent set of skills informed by experts who have defined what they believe is needed to succeed in a work role or academic discipline. These work well for younger learners with limited work experience. They do not always work well for older learners needing a small amount of upskilling to stay current in their role. They also do not empower lifelong learners to self-identify and gain new skills which may not fit into traditional ‘coherent’ groupings of learning. Similarly, especially if offered full time on campus, larger qualifications do not always support mature learners wanting to enter new industries to upskill as quickly as possible, by repeating learning related to skills they have already mastered.

The need for upskilling and retraining is relevant across all levels of the NZQCF, where there has historically been a strong link between qualification level and qualification type. Qualification types are specified on the NZQCF and consequently stakeholders are accustomed to thinking of, for example, Level 7 learning being degree level study, associated with 360 credits worth of learning.

The development of micro-credentials aimed to disrupt the close association of level, qualification type and related credit value by encouraging short, relevant training at any level of the Framework. For example, one of the first micro-credentials, approved as a pilot in 2018, was a Level 9 60-credit micro-credential in self-driving car engineering, different to a traditional Level 9 two-year (180 or 240 credits) Masters level programme.

The intention was to encourage more lateral thinking about the qualification system, the relevance of education and training and the place of end-users. The goal was to shift policy, funding and regulatory settings that may have privileged the interests of tertiary education providers over end-users of education and training.

Since their introduction in 2018, micro-credentials in Aotearoa New Zealand have proved more popular at lower levels of the Framework. Universities have been slower to develop formal micro-credentials (New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2022a). This contrasts with the European experience, where the emphasis for micro-credentials has been at university rather than vocational level (European Training Federation, 2022). Evidence of demonstrable support from industry, employer or community is a key criterion in micro-credential approval, so it makes sense that vocational education organisations with strong industry links would be early adopters.

Aotearoa New Zealand is undergoing major reforms of its vocational education system. These reforms include establishing Workforce Development Councils and Regional Skills Leadership Groups to ensure the relevance of education products - full qualifications, micro-credentials and skills standards (the core building blocks of vocational qualifications). Regional Skills Leadership Groups understand labour market and skills priorities and how to achieve them, as well as labour market and skills challenges and how to overcome them. Workforce Development Councils work with industry and community partners to set standards, develop qualifications and help shape vocational education curricula.

Originally providers had the legislated ability to develop micro-credentials. Now the newly created Workforce Development Councils also have this ability, and it is anticipated they will take up this role for vocational education to ensure a suite of education products that meets the evolving needs of industry and lifelong learners. Both Workforce Development Councils and Regional Skills Leadership Groups indicate strong support for micro-credentials to improve work readiness and recognition of prior learning. Well-designed micro-credentials can support these aims, but so can well-designed larger programmes.

Communication is an important part of any change process. A 2019 survey of European students, educational institutions, governments and employers found that most respondents did not know what the term micro-credential meant (Brown et al., 2021). A 2020 survey in Ontario, Canada noted that only one in four of the working age Canadian respondents had heard of the term micro-credential and even fewer knew what it meant, but that more than two thirds were interested in the idea of short skill-focused learning (Colleges & Institutes Canada, 2021). This paper is one step NZQA is taking to help stakeholders better understand micro-credentials and their role in the overall qualifications and credentials system.

A key aim of formalising shorter courses of study was to be able to respond quickly to emerging labour market needs. Competencies defined in urgent upskilling-focused micro-credentials can then be fed into updates of full qualifications to keep those current. Initially, NZQA stipulated that micro-credentials needed to be reviewed annually, with the aim of continuing to be agile and responsive to industry and community needs. Experience has shown us that yearly review is too frequent, given micro-credentials’ ongoing relevance beyond one year and resourcing implications for all parties.

NZQA’s approval criteria for micro-credentials originally included ‘not typically duplicating current quality assured learning already approved by NZQA’. This was an attempt to minimise duplication, which is inefficient and makes it difficult for employers and learners to understand what education products are available and which one is most suitable for their needs. In practice, along with an inability for micro-credential owners to accredit other providers to offer a micro-credential, this Rule risked removing competition, by giving the first provider to develop a micro-credential a monopoly. Given other changes happening in the national skills system, this Rule has been interpreted liberally. With legislative changes - and as Workforce Development Councils increasingly own development of an appropriate suite of national educational products - this issue is anticipated to disappear for vocational qualifications.

Assuring quality

The New Zealand Productivity Commission saw a need for learners to be able to accumulate portable credentials that could recognise their existing skills, support ongoing upskilling at higher and lower levels over a person’s lifetime, and help people move between jobs. They recognised that small, industry-provided courses could respond more quickly to change. However, they concluded that NZQA approved micro-credentials would be more likely to support movement between industries because they offer external validation (New Zealand Productivity Commission, 2020).

Similarly, Colleges and Institutes Canada, in their 2021 review of the status of micro-credentials in Canada said ‘For micro-credentialed training to be effective, it must be recognized and valued in the labour market. Potential employers must understand what the credential means and be assured that they can trust the quality of delivery as comparable to that of other programs’ (Colleges & Institutes Canada, 2021, p. 2).

One of the most thoroughly worked-through definitions of micro-credentials to date states that a micro-credential (Oliver, 2021, p. 4):

- Is a record of focused learning achievement verifying what the learner knows, understands or can do;

- Includes assessment based on clearly defined standards and is awarded by a trusted provider;

- Has stand-alone value and may also contribute to or complement other micro-credentials or macro-credentials, including through recognition of prior learning; and

- Meets the standards required by relevant quality assurance.

While some jurisdictions have adopted a loose approach to specifying the parameters of micro-credentials (as reflected in the above draft common definition undertaken for UNESCO), Aotearoa New Zealand deliberately opted for a tighter, more specific definition. At the heart of the approach is regularising sub-qualification training through extending the prescriptions of the NZQCF. NZQA does not consider there is any inherent reason why a tight or loose approach to defining a micro-credential is more, or less, desirable. It depends on the qualifications system context of a specific jurisdiction. For Aotearoa New Zealand, at this point, we consider a more prescriptive approach better supports quality assurance, official recognition and portability for the learner.

As part of the approval process, a micro-credential is levelled against the NZQCF and assigned to the relevant level of the framework. An approved micro-credential will have a credit value of no fewer than five and no more than 40 credits (50 to 400 hours of implied learning), include formal assessment, and be developed to meet an explicit employee, professional association, iwi or community need.

Types and numbers of credentials are increasing across the world, driven in part by the growth in global online provision of short training courses. Therefore, it is becoming more difficult for employers to understand awards and use them to evaluate the skills applicants bring. Micro-credential developers can apply for approval at any level on the NZQCF. In this way, employers and learners can understand the duration (credits) and the complexity (level) of the training, and learners can benefit from improved recognition of the learning completed.

Standard qualification system quality assurance processes integrate ‘front-end’ approval with self-assessment of delivery. Providers maintain the choice to use kaupapa Māori based quality assurance processes or ‘mainstream’ processes. There are two main differences in rules between qualifications and micro-credentials approval. The first is a commitment to a shorter turnaround time for approval of micro-credentials. The second is concurrent approval of the credential and how it will be taught and assessed. This achieves the intended ‘quick to market’ education products outcome, at the same time as assuring quality and defining value.

Since 2018, a small number of micro-credential applications have not been approved. The quality of applications seems to be improving over time as micro-credential developers better understand the requirements.

We have extended a service to organisations who are not registered as education providers to obtain an ‘equivalency’ assessment. This enables stakeholders to understand the value (duration and complexity) of training even when the delivery and achievement of the micro-credential is not quality assured by NZQA. In this way, we supplement improvements to our national, formal awarding system with processes to enable employers and learners to benefit from other disruptive education models which have potential to address our tertiary education challenges. Equivalency has been recognised for provision such as MOOCs and industry awarded short courses building towards fuller qualifications (Brown et al., 2021).

Increasing equity

Education - particularly vocational education - alternates between focusing on the manpower needs of industry, and on social justice and individual self-development (Burke, 2022).

In seeking to understand how technology affects jobs and employment, the New Zealand Productivity Commission saw micro-credentials as an important part of making the training system more accessible and flexible, thereby better meeting the needs of learners (2020). The European Training Federation noted the potential for micro-credentials linked to qualifications to ‘provide additional learning opportunities for vulnerable groups and those who have dropped out of formal education’ (2022, p. 6). Australia’s National Micro-credentials Framework saw a need to support lifelong learners reskill and upskill, to minimise the dislocation and mental health challenges arising from industry disruption (Australian Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2021). A 2018 survey of US companies’ use of educational credentials in recruiting staff noted that the time and financial costs of obtaining a micro-credential are lower than gaining a full qualification (Gallagher, 2018). Self-paced or competency-based programmes allow someone with prior knowledge or experience to complete even more quickly. However, costs were still prohibitive for some learners, who might not be eligible for financial support to study shorter courses (Gallagher, 2018).

The original focus in Aotearoa New Zealand’s move to micro-credentials was to quickly respond to changing labour market skill needs, at the same time providing lifelong learners with relevant, portable, recognised credentials. Increasingly, NZQA is considering the role of micro-credentials in social justice through enabling education and training for disadvantaged learners at all stages. To achieve this purpose, we need flexible pathways based on smaller chunks of learning that can be stand-alone or ‘stacked’ into qualifications. This requires consideration of how best to ‘plug in’ micro-credentials within a coherent programme of study leading to a larger qualification, and how larger qualifications might be able to be disaggregated into smaller credentials (Boud, 2021).

A stakeholder group from the food and fibre sector has completed a stocktake of all short courses across their sector (formal programmes, NZQA registered courses and small workshops and badges). Next, they plan to review the value of each short course and how to stack them towards larger qualifications. The group says ‘it makes sense that if someone in an industry has done a whole lot of short courses, that they be able to use those as credits to a bigger qualification’ (“Organising Micro-credentials,” 2022).

It raises questions regarding the relative importance of gaining ‘coherent’ groupings of learning through larger qualifications versus gaining a sub-set of skills through micro-credentials to be able to enter the workforce more quickly. The former risks introducing barriers to completion for some learners. The latter risks learners being limited in their career progression, which can be managed by supporting learners to complete new micro-credentials through flexible workplace learning models. This is an illustration of the interplay between the development of education products that enable flexible learning pathways and the associated delivery models necessary to achieve equitable outcomes. Such changes offer benefits to all lifelong learners.

Online learning, offered by global companies such as Coursera, Udacity and EdX, has contributed to the growth in uptake of micro-credentials. More flexible delivery models offer disadvantaged learners the opportunity to gain employment after having developed, and been recognised for, a specific level of skills, and to potentially achieve a full qualification while working. This requires a micro-credential to be a standalone product of value to an employer which can be stacked towards a larger qualification, facilitating full participation within an industry over time.

Funding policy is a factor in determining whether micro-credentials contribute to greater equity. In 2019, soon after micro-credentials were introduced, they became eligible for government funding. Two years later, an initial funding limitation of 5% of overall funding was removed to enable an even greater uptake of micro-credentials. At present, learners studying micro-credentials are not eligible for the student loans or allowances they can receive when studying full qualifications. However, they may be eligible for the Fees Free initiative, which enables first time learners doing their first year of study at tertiary level to study without paying fees.

One of the challenges Aotearoa New Zealand faces in its equity aspirations is the present trend for micro-credentials to be developed for those already in the workplace. This privileges those already in employment and in jobs that require upskilling, over those who are unemployed or in jobs overtaken by technology.

Sustainability

It is important to drive change in a sustainable way that provides value for money for government, employers, communities and learners.

The introduction of micro-credentials is part of the evolution of Aotearoa New Zealand’s vocational education system, in which smaller awards have always had a place. In 2011, short courses became training schemes, in 2018 we introduced micro-credentials and in 2022 training schemes will become micro-credentials. Vocational qualifications can already be as small as 40 credits and are developed in consultation with industry to target specific skill gaps relevant to jobs. However, for degree and postgraduate programmes, introducing micro-credentials offers a more radical change, and uptake has been slower.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, we are fortunate to have existing national processes and infrastructure to support change. Qualification developers and providers follow the same processes to assess labour market needs and the economic business case for provision of shorter programmes of study as they use for full qualifications. Similarly, standard funding arrangements apply to micro-credentials, although with some limitations. We have enabled micro-credential development but not introduced separate funding to stimulate it, such as that available in other jurisdictions. For example, in Canada, three provincial governments have launched targeted funds to promote micro-credentials development (Colleges & Institutes Canada, 2021). Similarly, the Irish Universities Association received €12 million to develop a national micro-credential system (Brown et al., 2021).

A 2022 report explored the dynamics behind digital skills training, an example of a skills response to technological innovation, noting that the most common barrier to digital skilling was employers’ and learners’ limited awareness of available training options. Another barrier was lack of awareness of the necessary digital skills. The report suggested that governments have a role to play in providing stakeholders with clear information on options for training and skills frameworks that define skills in relation to occupations (AlphaBeta, 2022).

Aotearoa New Zealand had the advantage of an existing national infrastructure to define and provide information on micro-credentials. Initially, NZQA provided a list of micro-credentials, but has now developed a database searchable by key word and educational organisation that outlines for each micro-credential its aim, learning outcomes and who can deliver it (which is accessible through the NZQA website). This system builds on the same infrastructure used to provide details for full qualifications on the NZQCF. As a comparison, Australia has committed more than AUD4 million to develop a National Micro-credentials Marketplace to standardise information across the country and effectively share this with job seekers and employers.

We want to know that we are achieving value through the changes and investment we have made. A challenge in innovating is that standard data collection processes may not support the way increasingly diverse education products may be used by learners and the value derived by employers.

Aotearoa New Zealand gathers data on completions of programmes in which the government has invested. These are predominantly full qualifications supporting learners to begin a career. We also follow groups of individuals gaining qualifications to understand their future work and study patterns. However, at present, we only collect data on micro-credentials in which the government is investing. To understand their broader uptake by industry and learners, we will need alternative data collection methods. Ideally, we will define and gather data to understand their contribution to productivity and equity, and therefore their return on investment for stakeholders. Case studies and tracer studies can supplement quantitative data to help us round out our understanding.

Conclusion

Micro-credentials promise value across the measures of relevance, quality, equity and sustainability. NZQA will continue working with partners across Aotearoa New Zealand’s skills system to keep adjusting its approach and settings to maximise benefits across these fronts.

As demonstrated in Improving relevance and responsiveness: New Zealand’s early micro-credentials journey (New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2022a), a good start has been made in terms of micro-credentials available in a diversity of fields, at sub degree levels of the NZQF and in different types of tertiary education organisation. There remain opportunities for significantly greater benefit, both in terms of responding to specific unmet skill needs and for micro-credentials to support learners’ achievement of full qualifications.

Returning to the theme of innovation, it is hoped that some approaches (e.g. duration, mode of delivery, and approaches to teaching, learning and assessment) within qualifications will evolve in response to the role of micro-credentials in focusing on end-user needs and relevance.

References

AlphaBeta. (2022). Building Digital Skills for the Changing Workforce in Asia Pacific and Japan (APJ).

https://alphabeta.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/ aws-apj-en-fa-onscn.pdf (external link)

Amundsen, D. (2020). Sixty Years of Adult Learning in Aotearoa New Zealand: Looking Back to the 1960s and Beyond the 2020s. Australian Journal of Adult Learning 60(3), 492 – 514.

Australian Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2021). National Microcredentials Framework.

Boud, D., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2021). The Move to Micro-credentials Exposes the Deficiencies of Existing Credentials. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 12(1), 18 – 20.

https://ojs.deakin.edu.au/index.php/jtlge/article/ view/1023/1018 (external link)

Brown, M., Nic Giolla Mhichíl , M. ., Beirne, E., & Mac Lochlainn , C. (2021). The Global Micro-credential Landscape: Charting a New Credential Ecology for Lifelong Learning. Journal of Learning for Development, 8(2), 228 – 254.

https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/525/617 (external link)

Burke, G. (2022). Funding Vocational Education in Australia: 1970 to 2020. VET Knowledge Base.

Colleges & Institutes Canada. (2021). The Status of Microcredentials in Canadian Colleges and Institutes: Environmental Scan Report.

Conway, P. (2018). Can the Kiwi Fly? Achieving Productivity Lift-off in New Zealand. International Productivity Monitor, 34(1), 40 - 63.

Earle, D. (2020). Qualification level match and mismatch in New Zealand: Analysis from the Survey of Adult Skills. Ministry of Education.

European Training Foundation. (2022). MicroCredentials are Taking Off: How Important are they for Making Lifelong Learning a Reality? Policy Brief, 1, 1 - 8.

Gallagher, S. R. (2018). Educational Credentials Come of Age: A Survey on the Use and Value of Educational Credentials in Hiring. Northeastern University.

Gluckman, P., Bardsley, A., Spoonley, P., Royal, C., Simon-Kumar, N., & Chen, A. (2021). Sustaining Aotearoa New Zealand as a Cohesive Society.

Green, S., & Schulze, H. (2019). Education Awa: Education Outcomes for Māori.

Hayes, H. G., Witkowski, S., & Smith, L. (2016). Failing Forward Quickly as a Developmental Evaluator: Lessons from Year One of the LiveWell Kershaw Journey. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 12(27), 112 – 118.

https://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/ view/435/426 (external link)

Intelligent Failure Learning & Innovation Loop. (n.d.). Fail Forward.

Ministry of Education. (2020). Best Practice for Teaching Pacific Learners: Pacific Evidence Brief 2019.

New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2017). New Models of Tertiary Education.

New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2020). Technological Change and the Future of Work: Final Report.

New Zealand Productivity Commission. (2021). Productivity by the Numbers.

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2022a). Improving Relevance and Responsiveness: Aotearoa New Zealand’s Early Micro-credentials Journey.

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2022b). University Entrance: Do Current Programmes Lead to Equity for Ākonga Māori and Pacific Students?

Oliver, B. (2021). Draft Preliminary Report, A Conversation Starter: Towards a Common Definition of Micro-Credentials. UNESCO.

Organising Micro-credentials A Priority for Food and Fibre Sector. (2022, June 10). Scoop Business.

Reid, A., Schulze, H., Green, S., Groom, M., & Dixon, H. (2020). Whano, Towards Futures that Work: How Māori canLead Aotearoa Forward.

Spoonley, P., Peace, R., Butcher, A., & O’Neill, D. (2005). Social Cohesion: A Policy and Indicator Framework for Assessing Immigrant and Host Outcomes. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 24(1), 85 - 110.

Stats NZ. (2014). Disability Survey: 2013.

https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/disability-survey-2013 (external link)

Stats NZ. (2018a). 2018 Census Ethnic Group Summaries: Pacific Peoples.

Stats NZ. (2018b). Wellbeing Statistics: 2018.

https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/wellbeing-statistics-2018 (external link)

Stats NZ. (2020a). Education Outcomes Improving for Māori and Pacific Peoples.

Stats NZ. (2020b). Measuring Inequality for Disabled New Zealanders: 2018.